When sparks fly

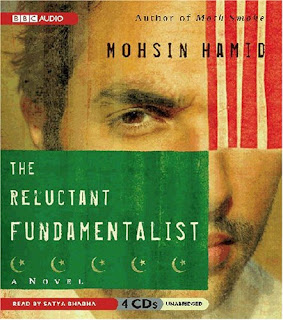

When sparks flyAuthor: Mohsin Hamid

Genre: Fiction Price: 295

Published in : 2007

Price: 295

I've been trying to read some good Pakistani writing in English for a while now. And I'm glad I made an introduction with Mohsin Hamid's The Reluctant Fundamentalist, who earlier wrote Moth Smoke, a novel, which Rahul Bose is now adapting into a film.

Lately, there has been a flowering of young Pakistani writers like Hamid and Kamila Shamsie (Cartography, Salt And Saffron), and in many ways, this is the first literary stirring that the country is witnessing.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist looks at the increasingly volatile and precariously balanced relationship between the West (United States) and East (South Asian Muslim countries), and how without a certain sense empathy, this equation will steadily spiral downwards.

Interestingly, Hamid’s point here is that a feeling of fundamentalism can arise in the unlikeliest of people, when they feel pushed to a corner.

The novel’s protagonist, Changez is a Princeton graduate, has led a charmed life back in Pakistan and is all set for a enviable career in New York.

He bags a job with one of the premium companies of the city, Underwood Samson and in a short while, is recogonised as one of the firm’s brightest young talents.

If he thought life couldn't get better, he’s proved wrong. Soon enough, he falls in love with Erica, a rich, pretty and artistically inclined American girl. But this relationship is fraught with troubles. Though there is a great deal of affection and even curiosity between Changez and Erica about their respective backgrounds, theirs remains a largely unfulfilling bond. Erica cannot get over Chris, her boyfriend who died some years back and thereby, can never fully 'open up' (sexually too) with Changez. In a moment of frustration and even resentment, the latter asks her to imagine him as Chris and make love.

This is when you realize that Hamid’s constructed an allegory here. Erica stands for America (Erica), and symbolises the deep infactuation Changez feels for her on certain levels. His own company is called Underwood Sampsons, standing for US, a highly competitive firm with a narrow focus on its own progress.

Erica's inability to accept Changez, unless he 'becomes' Chris, quite clearly, hints at the country's unwillingness to accept the former’s identity for what it primarily is.

Till this point, Changez largely shares a love-hate equation with the US. He loves being a New Yorker, both his high-flying job and girlfriend fill his heart with a sense of pride. However, at the same time, Hamid's protagonist is no pushover. Clearly, Changez has a mind of his own and feels a deep sense of attachment to his motherland (Pakistan). The fact that bright minds like him have to desert their own country, to fill the coffers of an already overdeveloped, supercilious country, leaves him frustrated.

This realisation further dawns upon him when 9/11 occurs and Changez feels a strange sense of thrill at 'someone bringing America to its knees'. From there on, life is never the same and his disenchantment with America is complete.

Erica is afflicted with a mental illness and slowly fades away (literally) from his life. This is a period when Changez also develops a certain rebellious streak, refusing to either cut off his beard or focus on his job. News of America's attacks on Afghanistan, Pakistan's closest neighbour fills his heart with resentment and from there on, it's only a matter of time before he loses his job.

Once back in Pakistan, Changez becomes a professor at a University, 'who makes it his mission on the campus to advocate Pakistan's disengagement with America'

Though the book does not, in any way, glorify fundamentalism, it subtly points at how sparks of fundamentalism can be ignited in the most placid looking people and circumstances. Hamid succeeds in making his central character-Changez engaging from the word go and it helps that this book is a rather compact, slim one, without too much rambling.

But, while Hamid's attempt at constructing an allegorical narrative is interesting, it is hardly intrusive enough to lend the story any kind of depth. If anything, it slackens its dramatic pace, making it both tedious and essayist.

On the other hand, Changez's professional life has been treated with great flair and understanding.

There are great stories to be written on the increasing east-west gulf and the growing feelings of mistrust between both continents. The Reluctant Fundamentalist only skims the surface, but nevertheless Hamid does enough to prove that he's a writer to watch out for.